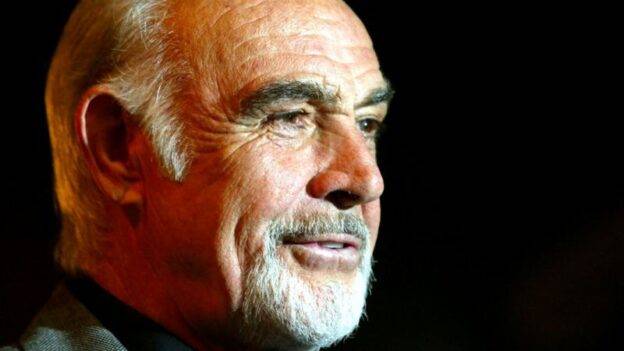

As if 2020 wasn’t already a rotten enough year, legendary Scottish actor and screen icon Sean Connery passed away on October 31 at the ripe old age of 90. The New York Times obituary is here.

While it’s only natural that the majority of tributes for this great man focused on his career and character-defining creation of James Bond on the big screen — a role that he will forever be linked with through his singular excellence even though he had not played the part in 37 years — Connery was at best ambivalent about this seminal pop culture cinematic contribution. He worked hard both during and after his time as 007 to establish a screen persona distinct from the debonair and dangerous secret agent. While Bond was undoubtedly his ticket to the big time, as early as 1964 Connery was looking to expand his horizons as an actor with his intriguingly complex role as Mark Rutland in Hitchcock’s Marnie (1964) breaking down a neurotic and sexy Tippi Hedren. Even as his career-defining work as Bond turned him into a 1960s pop culture icon on a level with the Beatles, Connery bristled at the confining nature and potential career cul de sac of such a monolithic character. Indeed, he was right to worry that his entire career would be defined by Bond and he would never be able to be perceived or accepted by the public in any other manner. Famously unhappy during location filming in Japan for 1967’s You Only Live Twice and the suffocating and hysterical adulation of his fans and paparazzi there, Connery shockingly renounced the role and passed on making the next film in the series, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. While 1969’s OHMSS is actually one of the greatest Bond movies in terms of plot, featuring complexities of character that wouldn’t be plumbed again until Timothy Dalton’s brief, unsuccessful tenure in the late ’80s and then the rampaging success of Daniel Craig’s current edgy and penetrating portrayal, and one-off Bond George Lazenby did a perfectly capable job, one still wonders what kind of special performance Connery might have given in that final scene mourning the death of his new bride Tracy (the lovely, late Diana Rigg), a victim of Blofeld’s vengeful drive-by shooting.

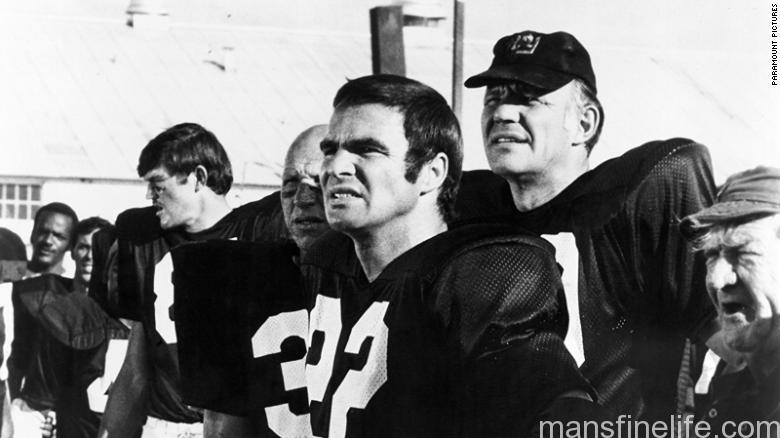

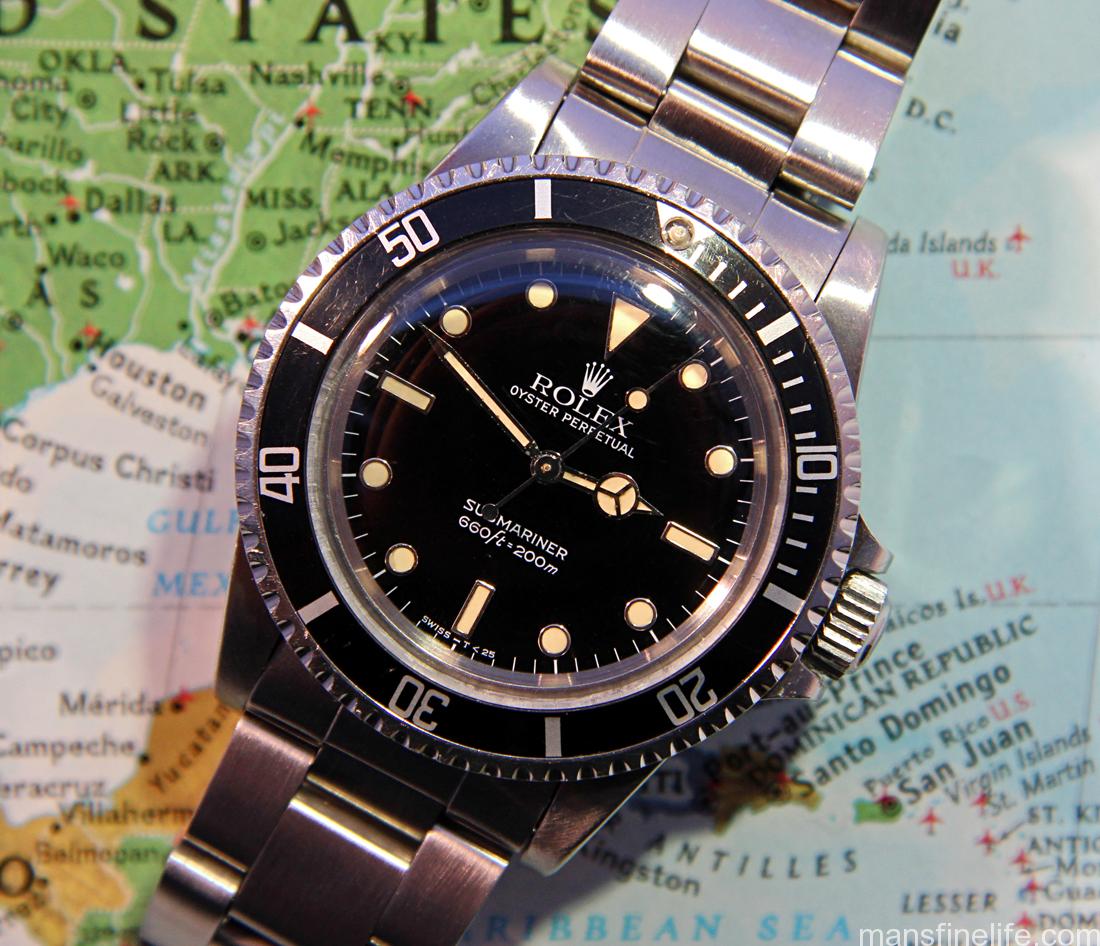

Alongside Michael Caine getting carried away with their success in John Huston’s The Man Who Would Be King

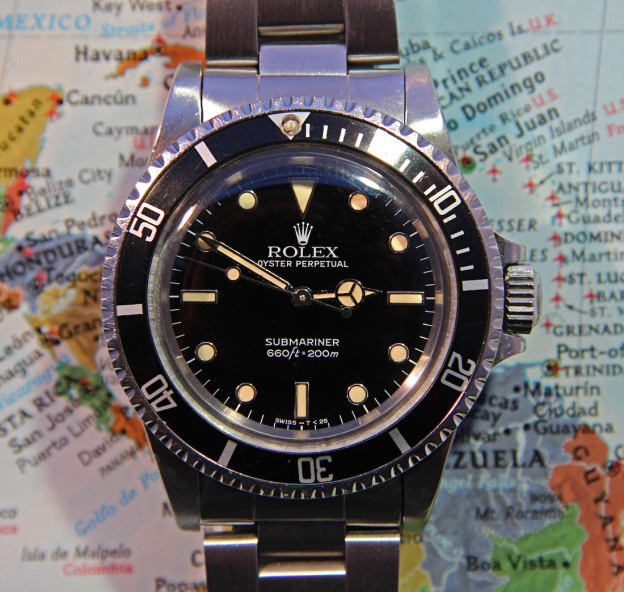

After Lazenby self-destructed, Saltzman & Broccoli lured Connery back into the EON Bond fold by means of the then-unheard of amount of $1.25 million dollars for the somewhat tacky but enjoyable Vegas romp, Diamonds Are Forever (1971). Pocketing his money like any good Scotsman, Connery bid adieu to Bond and the requisite toupee for the remainder of the 1970s, embarking on a career no longer entirely beholden to the super spy. With his receding hairline a near declaration of liberation, Connery built on the grittier realism of Bond-concurrent performances in The Molly Maguires (1970) and especially Sidney Lumet’s excellent The Anderson Tapes (1971), to craft an equally charismatic but much more jaded and cynical character on screen, particularly the latter’s swaggering, unrepentant thief at large in 1970s New York City. Sure, Connery was still bigger than life, as witness his game participation in the bonkers sci-fi of Zardoz (1974) running around in only a red loincloth for most of the picture; the fantastic Kipling-derived adventure of John Huston’s The Man Who Would Be King (1975), finding the perfect partner for fortune hunting in Michael Caine but getting fatally carried away as a pretend god; and a very Scottish Berber bedeviling Theodore Roosevelt from afar in The Wind and the Lion (1975). But his finely crafted performances, natural as ever, now revealed men with serious flaws and character defects that made them all the more interesting, most notably delusions of grandeur and a true and sometimes self destructive soft spot for the ladies (unlike Bond’s love ’em and leave ’em ethos).

Connery embraced his middle age with Robin and Marian (1976), Richard Lester’s touching and elegiac reimagining of a post-Crusades Robin Hood returning to find Maid Marian, played by the wonderful Audrey Hepburn, a devoted nun and Nottingham unacceptably under the thumb of his old foe, the Sheriff, played by the always compelling Robert Shaw. Shaw was that rare match in equalling Connery’s natural machismo and toughness, as he had been back in the From Russia With Love days when he was a homicidal defector trained by the Russians to kill Bond. Sir Sean was back at his lighter, mischievous best in Michael Crichton’s excellent 19th Century heist extravaganza, The Great Train Robbery (1979), wonderfully paired with the always unique and equally roguish Donald Sutherland as two particularly brilliant and stylish thieves. After notable cameos in the star studded but bloated A Bridge Too Far (1977), one of several possible suspects for Poirot to consider in Murder on the Orient Express (1974), and the very trippy and enjoyable 1981 Terry Gilliam opus, Time Bandits, where he was perfectly cast as a fatherly Agamemnon, Connery gave another terrific lead performance in the criminally underrated space “western” Outland (1981), laying down the law against long odds Gary Cooper-style, only with a mining station orbiting Jupiter as the scene of the showdown instead of a dusty frontier town. In 1983 he gave in to the siren song of a return to Bond in the “unauthorized’, non-EON Never Say Never Again, a remake of Thunderball, the rights of which were not controlled by the Fleming estate. While the film and Connery’s return as an aging but still peerless Bond have their undeniable pleasures, not least of the them very worthy opponents in Klaus Maria Brandauer’s flamboyant Largo, a lethal, leather-clad Barbara Carrera as femme fatale Fatima Blush and a delectable Kim Basinger as Domino, it was a strange lateral and some might say spiteful move by Connery. By making a Bond movie in direct competition with not only his old mates Broccoli & Saltzman but also then-current Bond, Roger Moore, it may have satisfied audiences for a double dose of 007 but it did nothing for his reputation as a somewhat irascible star prone to view producers as rip-off artists — certainly with some justification — and to cling to long-held resentments even against those who had helped launch his amazing career.

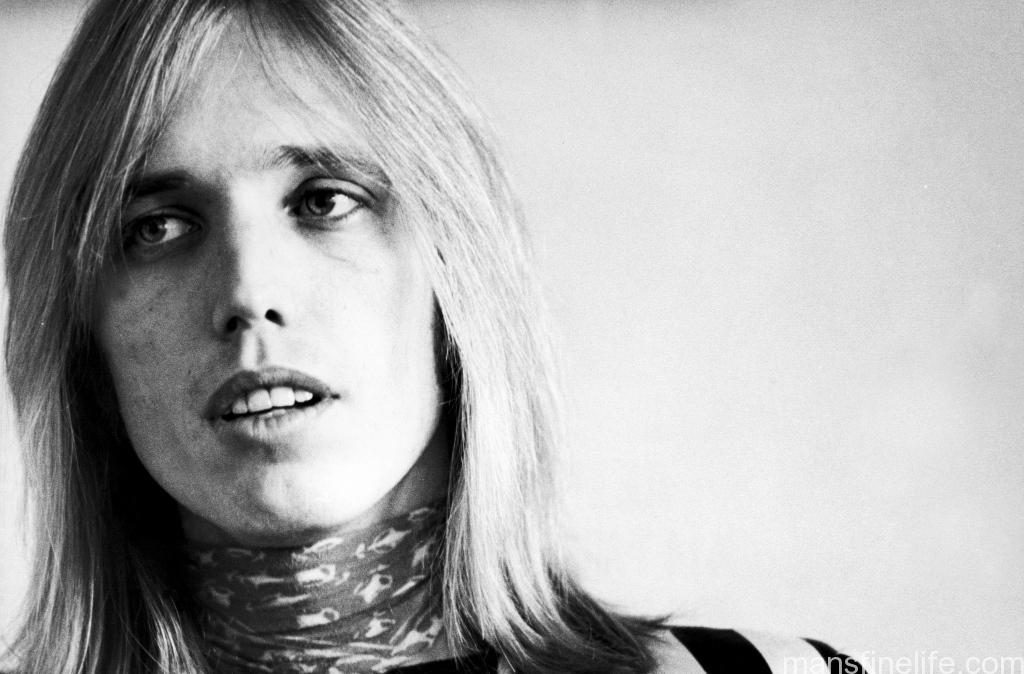

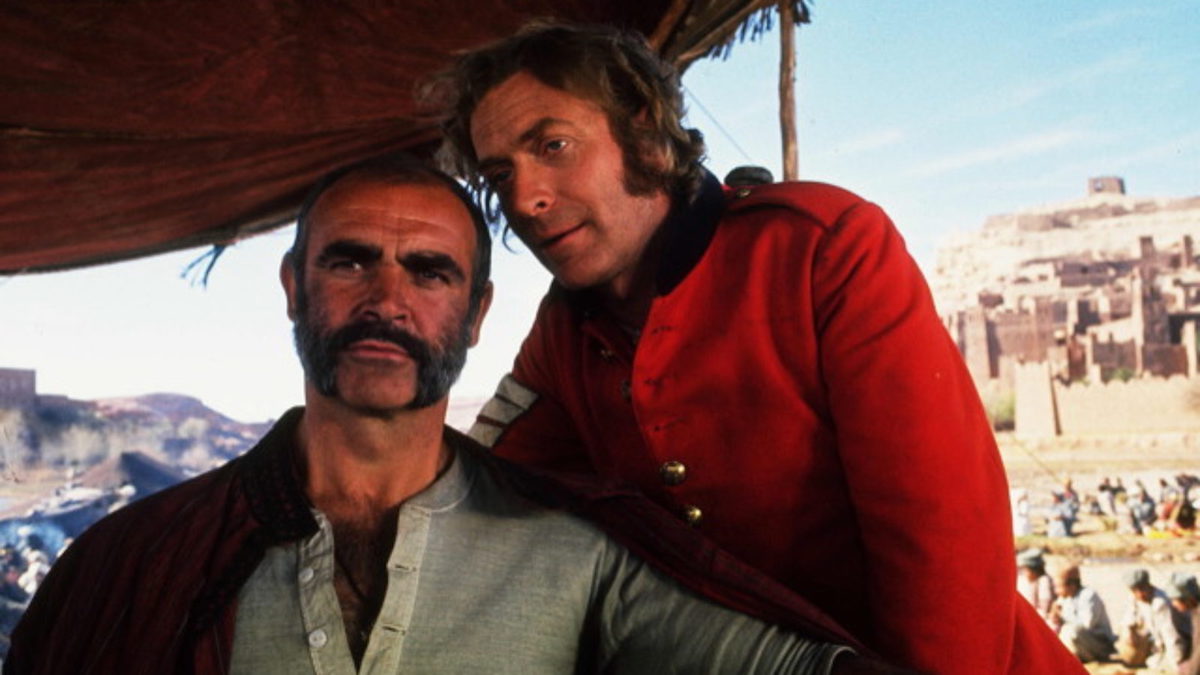

As a seasoned Irish cop instructing Kevin Costner’s green Eliot Ness on The Chicago Way in The Untouchables

Never Say Never Again was the last time Connery would revisit Bond and not only was he truly done with the legendary character but he embarked on an arguably greater chapter in his career, embracing his age to evolve into a kind of grand old man of Hollywood complete with gravitas and prestige to deliver to any larger than life role. After a fun, swashbucking turn in the silly but enjoyable fantasy of Highlander (1984) — as a Spanish swordsman, no less — Connery found the greatest critical success of his already highly accomplished career as the veteran Irish cop Jim Malone, teaching Kevin Costner’s green Eliot Ness “The Chicago Way” in order to hunt down Al Capone in Brian De Palma’s mega-hit The Untouchables (1987). The role, which the great film critic David Thomson noted culminates with his character “dying a samurai death,” won Connery that year’s supporting actor Oscar, his first and only Academy Award. It also opened up the floodgates of terrific parts to close out the ’80s and provided serious momentum well into the ’90s. He was Indiana Jones’s amusingly cantankerous dad in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), a skillful Soviet submarine commander matching wits with Alec Baldwin’s Jack Ryan in the smash hit The Hunt for Red October (1990) and a British publisher involved in Cold War intrigue and wooing Michelle Pfeiffer in the smart and intricate film version of Le Carré’s The Russia House (1990). As if that wasn’t enough of a third act, Connery also starred in and was executive producer on 1993’s Rising Sun, schooling Wesley Snipes in the ways of the Yakuza; likewise star and executive producer of the Simpson/Bruckheimer/Michael Bay summer blockbuster extravaganza The Rock (1996), as a long-imprisoned British commando freed to team up with Nicholas Cage to stop a group of rogue soldiers from turning Alcatraz into ground zero for a biological terror attack; and showing a lithe, cat-suited Catherine Zeta-Jones the ropes as a suave veteran thief planning a very high concept — and very high! — skyscraper robbery in Entrapment (1999). Even his last real film role, 2003’s very promising but troubled The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, offered a treat for Connery fans with his resonant portrayal of legendary adventurer Alan Quartermaine in twilight.

Connery’s cunning Soviet sub commander matches wits with Alec Baldwin’s Jack Ryan in The Hunt for Red October

So Sir Sean Connery’s passing offers us an opportunity not only to mourn the man who defined James Bond for decades of enchanted fans but also an actor of great daring and bravery who was not content to be solely pigeon-holed by Bond and actively worked to slip the potential trap of such a career-making role. That he succeeded so brilliantly is all the more proof that he was a film actor and a true movie star of the highest order, one of the last of that rare breed who was able to dominate cinema for a multi-decade span by the strength of a very fixed but adaptable screen persona. To revisit the Connery Bond films is always a pleasure and a delight of almost childlike enjoyment; to revisit his other great roles is to see the craft and skill of the mature actor whose joy in more complex parts was always evident on screen and therefore contagious to the audience, a multi-generational audience that never seemed to get enough of the great Scotsman. Godspeed, Sir Sean, and thank you for a lifetime of special performances. While we won’t see your like again we will always have your wonderful films and those many magnificent moments on screen to remember you by.