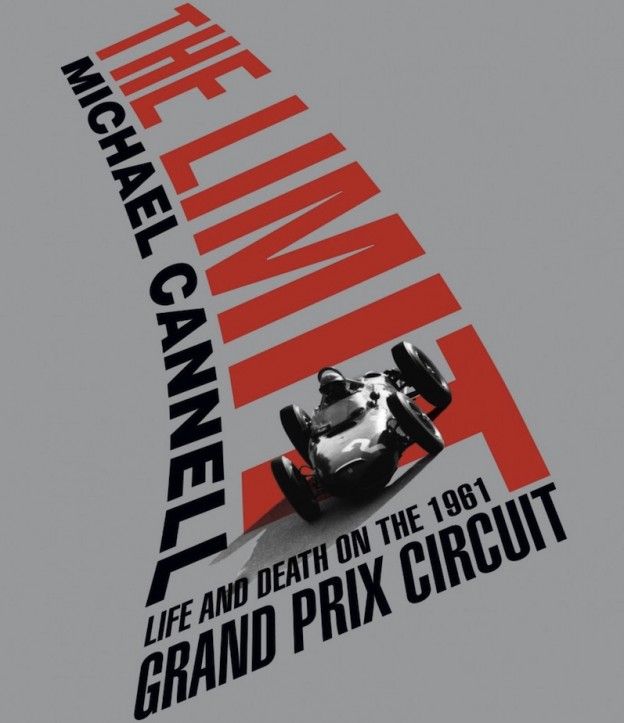

The winter interregnum between the major American and European motorsport seasons is the perfect time to wet one’s whistle for the upcoming action by catching up with the best books on racing. Easily qualifying for any serious fan’s motorsports library is Michael Cannell’s 2011 The Limit: Life and Death in Formula One’s Most Dangerous Era, which chronicles the epic battle between Ferrari teammates Phil Hill and Wolfgang von Trips for the 1961 F1 World Championship. While it relies heavily on the period reportage and essays of the great Robert Daley and those passages may be familiar to anyone who has read his seminal The Cruel Sport and Cars at Speed, Cannell’s volume still stands on its own merits. By focusing on the divergent personalities and biographies of the two friendly rivals and the common motivation that drove them to compete and succeed at the very highest level of the sport, a finely limned portrait emerges of not just the men but also the highly charged era in which they performed. And of course that charge came from the constant and absolutely genuine threat of crippling or fatal injury at every Grand Prix.

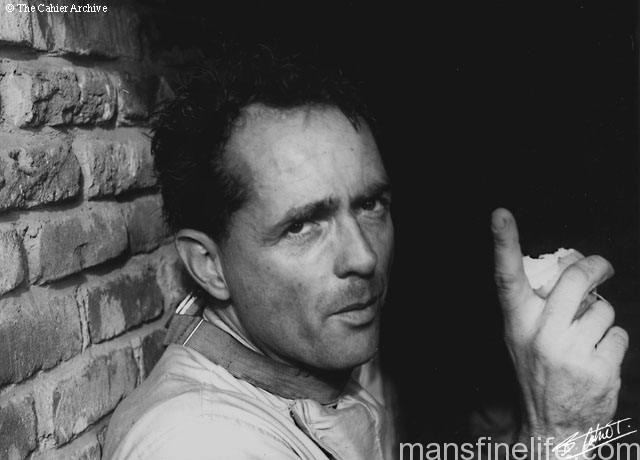

Phil Hill grew up a frail and insecure boy in Southern California, one who’s low self esteem was reinforced by a domineering father and an admitted incompetence at team sports. He only found his calling when an aunt gave him a Model T Ford to tinker with. As a teenager Hill quickly evolved into a prototypical hot rodder and he began getting paid to race, winning nearly every open sports car competition in California. Wolfgang von Trips was the heir to a noble German family who nearly lost everything during the cataclysm of World War II. When his family mansion near Cologne was occupied by American soldiers after Germany’s capitulation, von Trips became obsessed with the GI’s Jeeps and trucks. Eventually he would acquire a series of ever more powerful Porsches, which he raced with reckless abandon, earning him the nickname “Count von Crash.” Despite his proclivity to overstep the limit, or perhaps because of it, von Trips still managed to attract the attention of the Machiavellian Enzo Ferrari, founder of the greatest marque in motorsports. Hill, having left the oval racing-obsessed US to try his hand at European road racing, also managed to be pulled into Ferrari’s orbit by his early success with the Jaguar team. By the late 1950s both men were driving sports car races for the Prancing Horse and in line for a top-level factory Ferrari drive in Formula 1.

While graduating into the Ferrari F1 team may sound glamorous today, back in the classic era this was mainly achieved by having the drivers currently occupying those seats dying in action. So when the Scuderia’s Peter Collins was killed in 1958 at the Nürburgring, Luigi Musso was killed in the 1958 French Grand Prix and 1959 World Champion Mike Hawthorne retired after the season (only to be killed in a road accident while street racing a friend in England mere months later), that opened up seats for Hill and von Trips after their success representing Ferrari in grueling endurance races around the globe. By 1961, the second year of the then new rear engine specification and the debut of the brutally quick 156 “Sharknose”, Ferrari had the cars to beat and Hill and von Trips were the men driving them.

The Limit chronicles the 1961 season in race-by-race detail culminating in the tragic penultimate race at Monza, where von Trips came into the round needing only a 3rd place to take the Championship but instead crashed when he tangled with Jim Clark’s Lotus, his blood red Ferrari 156 going airborne and sluicing through the nearby crowd, killing von Trips and 15 spectators. Remarkably, during the “golden age” of Formula 1 this sort of carnage was not considered out of the ordinary and the race was not halted. Driving undeterred to victory, Phil Hill won the 1961 World Championship at Ferrari’s home race but in bittersweet fashion, unable to truly enjoy his accomplishment due to his teammate’s horrific death. With Ferrari’s decision to pull the team out of the final round at Watkins Glenn, the first-ever American Champion was even denied the opportunity to have his coronation in his home country. If you’ve seen the classic film Grand Prix you’ll know the final scene with the champion driver walking on a deserted and desolate track after a tragic race day, a scene that was essentially ripped from Phil Hill’s life (he was a key consultant on that film). It’s not hard to imagine that intense cinematic melancholy as Hill’s own experience on that dreadful day in Monza ruining what should have been his most glorious moment.

It is in its intense examination of these two competitors, as well as its powerful evocation of a bygone and frankly savage era in the sport, that The Limit is at its most effective. The handsome yet sensitive bon vivant von Trips, who was perhaps longer on charisma than skill, and the neurotic and difficult but undeniably brilliant Hill come to life on the pages of Cannell’s compulsively readable book. The inner drive that these two divergent men shared to push them to compete at the very highest level of their sport and risk it all for fleeting glory is integral to that bygone era. All of the elite drivers of that age seemed to have it. Death was around the corner at every race and those men cheerfully courted it on ridiculously unsafe circuits for barely any money and the cheers of a crowd that could only see a fraction of the action on the track. If we’re being totally honest, The Limit makes you realize that the great majority of people who pine for the “The Good Old Days” of Formula 1 are those who never had to drive those deadly machines in anger.