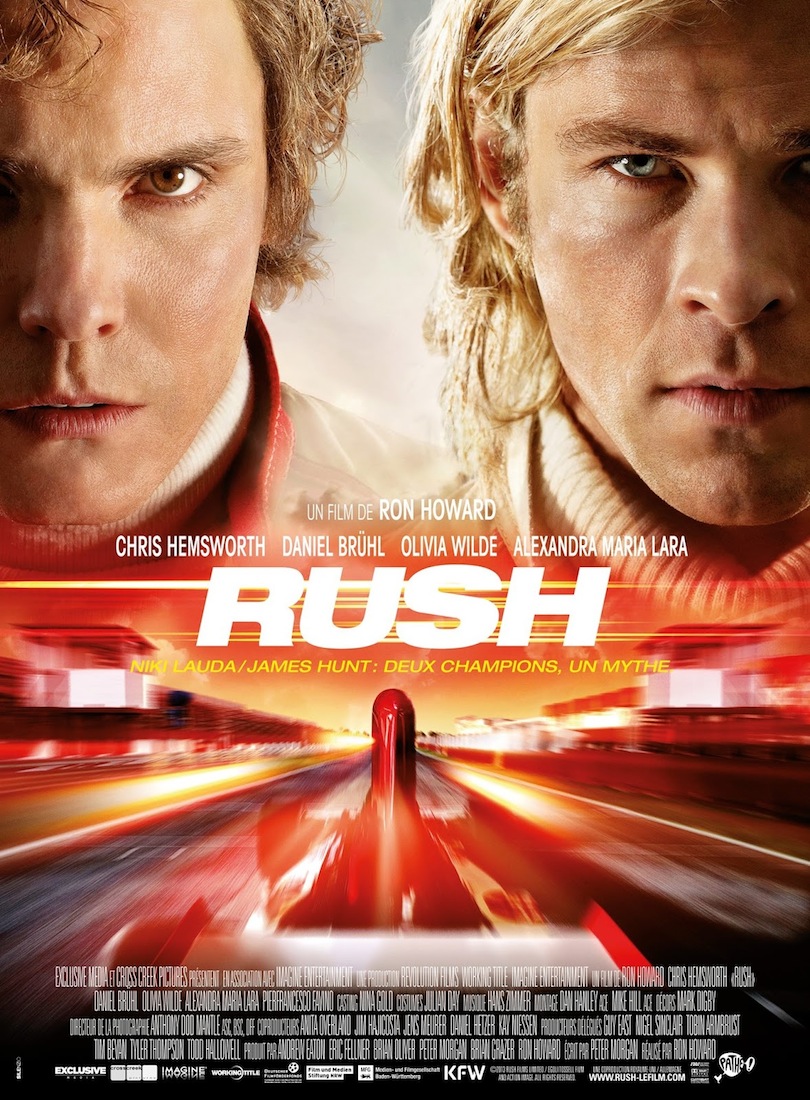

Ron Howard’s Formula One blockbuster Rush opened this past weekend across the country to generally very positive reviews from the critics and rather lackluster box office receipts. Most people, particularly Hollywood cognoscenti, will take that to mean that straight up racing films remain box office poison and that films about the Euro-centric world of F1 are particularly lethal. The thinking will be that unless you have Paul Walker and Vin Diesel blowing things up and destroying the bad guys in stolen hot rods while crashing them into jet liners, the general public is just not going to go to a straight racing movie no matter the high profile director or the technical virtuosity on display amongst all that vroom vroom.

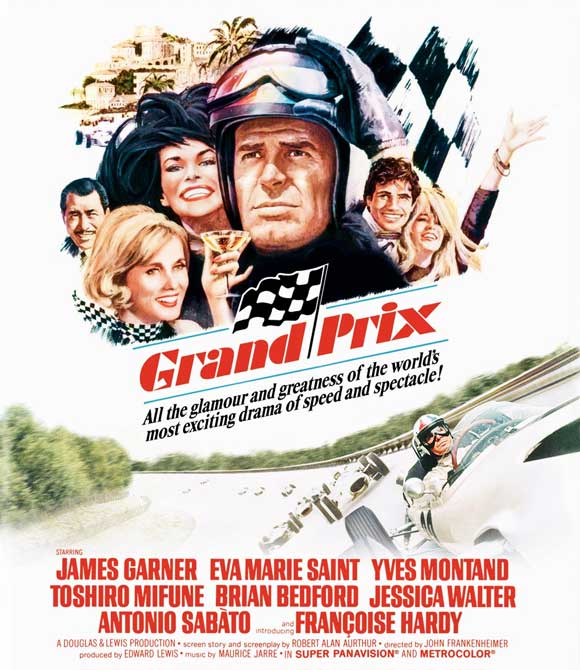

That’s all fine and good but the real issue is: Is Rush any good as a racing film, period? One can make a cult classic that does not attract great popular success and yet still have made something special, exciting and valuable to the cult itself. To truly evaluate Rush one has to compare it with arguably the only other really good racing film Hollywood has ever made, John Frankenheimer’s 1966 Grand Prix. (Obviously, the documentary Senna is indisputably fantastic but we are talking dramatized portrayals). Unfortunately it has to be said that in comparison Rush falls short, not on narrative but on the basis of visceral excitement.

Looking at footage from the two films is instructive of the difference between them. The trailer for Rush:

Where Rush is strongest is in the atmosphere of the 1970s celebrity racing scene–the glamor, the women, the looseness, the fun–and in the rivalry between the two drivers, in this case the legendarily louche Englishman, James Hunt, and the straight-laced Austrian mechanical genius, Niki Lauda. Make no mistake, the thrilling story of the 1976 F1 season is a classic and it is well told, with very good performances by Chris Hemsworth as Hunt and Daniel Brühl as Lauda (though we wish there was a bit more Olivia Wilde). Opposites make great antagonists and there were fewer men with more opposite approaches to their craft than Hunt & Lauda, even if the movie somewhat plays up their personal enmity, which Lauda insists was not so intense. (I had thought that Howard was also playing up Hunt’s partying, as well, but apparently if anything, he played it down!) The epic arc of that 1976 Drivers’ Championship is known well enough and forms the plot of the movie so I won’t spoil it for you if you’re not familiar with it. But suffice to say, it is well told and you really care about the characters, even as Howard cleverly shifts your sympathies from the playboy to the unattractive workaholic. Most praise worthy is that the real heroism in the film does not occur on the track but in the hospital during recovery from horrific injury. It is in these sequences that we get the definition of a pro driver’s real courage: the willingness to put it all on the line at the limit and risk the terrible consequences. And it is on these merits that Rush should be judged as most successful.

Where it comes up short is in the actual racing itself. And for a movie like this, an action adventure about the highest level of motor racing, this is the film’s fatal flaw as entertainment. Of course, we want to care about the main characters, to feel that they are fully fleshed humans who are reacting to the stresses and exhilaration of a super human undertaking. But Rush never really communicates that visceral excitement of what it means to be hurtling down a thin, curvy strip of asphalt at 170-200mph next to a pack of other cars holding their line next to you, behind you and to the side of you. The racing sequences are far too brief until late in the movie, so much so that it seems clear to me that at least 40 minutes or more of actual racing was cut out of the theatrical release, which only runs about 2 hours flat (one can hope that there will be a 2 hour 50 minute “Director’s Cut” released on DVD because what is shown is quite good at times). And so the early races of the season are shown in perfunctory (and exceedingly similar looking) montages with little context and only supertitles declaring “Niki Lauda 1, James Hunt 2” for the finish of the race, as well as copious sports play-by-play doing the heavy lifting on describing what’s actually happening. What is that first rule of cinema? Oh yes, if you’re explaining via narration or graphics, you’re usually losing. And in fact the actual later, more intense races also suffer from a sameness of visual presentation: the same facing-the-pit wall camera angle as the cars whiz by, same overhead angle to start the races, and a certain unexplained unfolding of the race, i.e. all of sudden Hunt is in first but how exactly did he get there except that the announcer has said he’s made an amazing charge through the field?

Which brings us to Grand Prix, the grandaddy of racing movies and one of John Frankenheimer‘s most underrated achievements. Let’s have a look at this 1966 opus via a very well-edited modern unofficial trailer:

Can you feel the difference between the movies already? One can make the argument that the plot is a bit more stodgy in the older film. But in fact, it is a very cleverly disguised synthesis of Phil Hill’s championship run in 1961 and his disappointments after leaving Ferrari, and so is very satisfying to those who know F1 history. And more importantly, the racing sequences are ten times more exciting. Now, it could come down to the differences between digitally manufactured/augmented effects for the driving and the ones Frankenheimer and Cinematographer Lionel Linden achieved with purely analog effects like a camera strapped to a following race car (a GT-40 usually driven by Phil Hill!). In fact, let’s look at this technique in action on the streets of Monaco:

It’s enough to make a gearhead’s heart go pitty pat, never mind how fetching Yves Marie-Saint and Jessica Walter are in the movie. But the superiority of Grand Prix also comes down to the variety of ways that Frankenheimer presents the different races, something Howard seems to really struggle with. In this way Frankenheimer devotes maximum screen time to the matter at hand–racing!–while presenting the contests with enough stylistic differences to render them always compelling to the viewer. For example, we open with the fantastic Saul Bass montage over the credits into the eventful Monaco sequence; another later race is presented as a ballet with only music and no engine noise, as the lovely wingless cars dance silently over the tarmac; Spa has rain on a stopwatch and carnage in the wet on the open roads of the Ardennes; and the final race at Monza is flat out speed, insane banking and tragedy. Of course, Frankenheimer has the advantage of not only the greatest era of F1 to work with as well as its best drivers (look for cameos by Hill, Graham Hill, Jochen Rindt, Bruce McLaren, etc) but also the very luxurious run time of 178 minutes that Howard for whatever reason felt was simply too long for a modern release. But it’s how Frankenheimer utilizes his assets, not least of which is the super wide screen 70mm Cinerama process, that makes Grand Prix so extraordinarily exciting and such an exemplar of racing.

Now I’m almost 100% certain that Ron Howard has many hours of exciting driving footage from Rush in the can that, whether analog or digitally augmented, would be every bit as exciting. I just wish he hadn’t tried to make his story so “respectable” that he left most of that on the cutting room floor. Rush winds up being a solid drama about two intense and highly skilled guys who happen to drive race cars. But the best movie about racing–its ethos, its pathology, its addictive thrill–remains Grand Prix.