If you’re a classic Rock fan with a particular interest in the 1960s like me then Becoming Elektra: The True Story of Jac Holzman’s Visonary Record Label by Mick Houghton is a must read piece of music history. As its long subtitle proclaims, Becoming Elektra is both a biography of legendary music executive Jac Holzman and also a testament to Elektra Records’ uniquely eclectic and pervasive impact on the popular music of the baby boomer generation. Houghton traces Holzman’s pioneering technical efforts and prescient eye for talent with admirable thoroughness from the Folk boom of the 1950s and early ’60s to the LA-based psychedelic Rock explosion of the late ’60s to the Soft Rock adult contemporary acts that came to dominate radio in the ’70s.

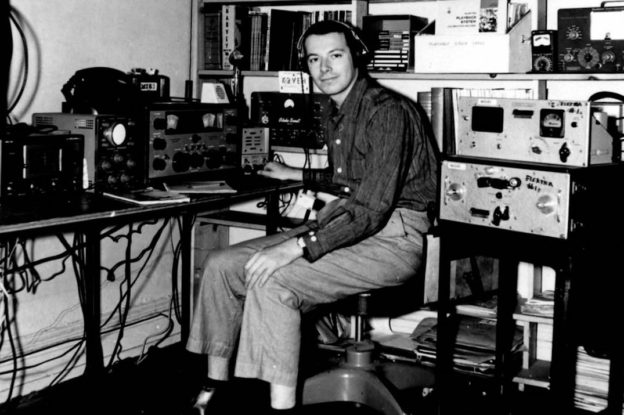

Most famous for signing The Doors, Holzman’s legacy is much more than that admittedly awesome feat. He comes across as a fascinating and driven guy with an unusually compassionate feeling for his artists, as well as something of a technical visionary and studio perfectionist with a super wide range of musical tastes. A native New Yorker from a reasonably prosperous family, Holzman returned to the city determined to make his mark in music after precociously forming Elektra while still in college. Like so many of his generation he found that the action was happening downtown in Greenwich Village, where he opened a record store in 1951 with a small recording studio in the back. Holzman’s soon realized that the sound on the records for the folk performers of the time was nothing like the richness of their live performances. So Holzman abandoned selling records and focused on seeking out unique new talents and then recording them to their best possible advantage. That became the Elektra signature throughout his years running the label.

The list of artists that Holzman corralled is nothing short of astonishing. In the folk era it included Village stalwarts like Jean Ritchie, Phil Ochs, Judy Henske, Fed Neil, Tom Paxton and Tom Rush, as well as reviving the career of Blues pioneer Josh White and discovering a young Coloradan with a big voice named Judy Collins. All the while, he also gave admirable attention to Classical music, particularly European chamber recordings, and what we now call World Music, at first though expert interpreters like actor/singer Theodore Bickel and exotic European acts like virtuoso Spanish guitarist Sabacas. Eventually Holzman realized that World Music and Classical deserved their own distinct platform and so he founded Elektra’s undeniably influential sister label, Nonesuch Records. Nonesuch, under the visionary leadership of the hand-picked Teresa Sterne, gave chamber music, global folk music and indigenous field recordings via the Nonesuch Explorer series, as well as early electronic music and emerging modern composers, their own self-contained label at budget prices, while Elektra continued to pursue more mainstream pop artists. Holzman’s breadth of interests were such that he even released a large collection of perfectly recorded sound effect records that became the industry standard in television and radio for decades to come. Amidst this early ’60s frenzy he also somehow found time to supervise the official Library of Congress recordings of Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly, remastering them from the original scratchy 78s and hand-editing out the clicks on the reel-to-reel tape transfers.

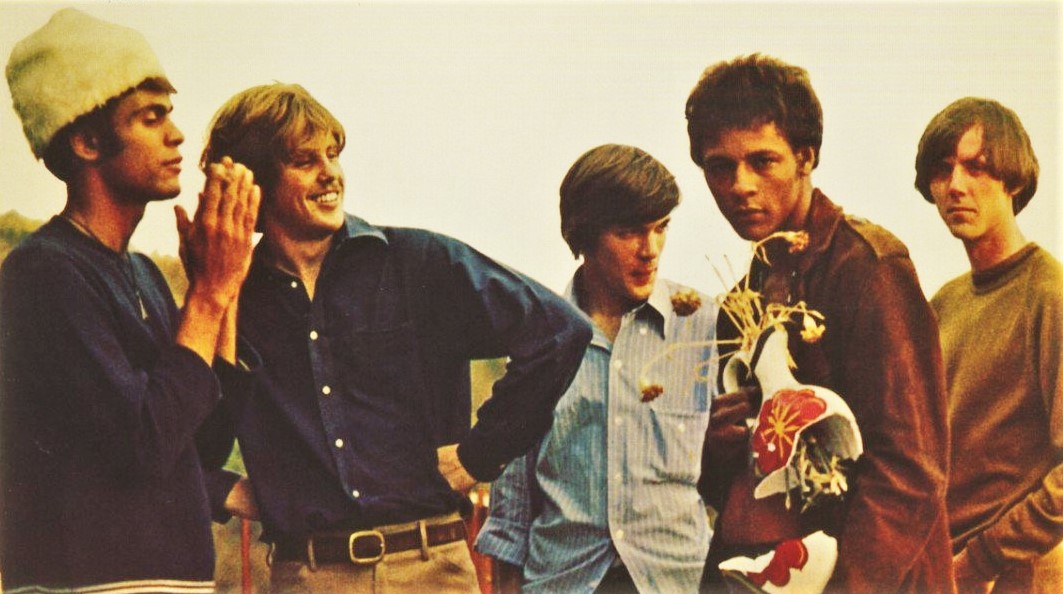

Love circa 1967 around the time of Forever Changes

Despite these already significant accomplishments Holzman really hit his stride in the mid-to-late ’60s discovering a mother lode of cutting edge Rock ‘n Roll via a preemptive foray to Los Angeles, where he sensed the music business was rapidly shifting. Holzman instinctively realized that in the wake of Dylan going electric the “pure” folk revival scene typified by Village coffeehouses was ossifying and running out creative impetus. Very much taken by the folk-rock fusion of the Byrds, Holzman’s first big LA signing was the legendary Love, the ne plus ultra of ’60s psychedelic bands and a massively important act in historical terms even if that wasn’t apparent to the general public at the time. And by hanging out with Love at LA’s Whiskey A Go Go club Holzman discovered the biggest act of his career and the one for which he will always be remembered.

If Love are the cult band of the late 1960s then The Doors are arguable the most successful and representative American band of that brief and tumultuous moment in Rock history. Saavily delayed by Holzman until January 1967 and employing the clever maneuver of a month’s worth of label exclusivity, their debut The Doors quickly became Elektra’s all-time best selling album and a bonafide rock phenomenon. The band uniquely captured the light and the dark sides of the flower power generation and seemed to transcend labels such as “hippy” entirely. Frontman Jim Morrison promised sex and death in equal measure and became a counter-culture Dionysus. And between Love and The Doors Jac Holzman saw his reputation as an influential trend-spotter and nurturer of cutting edge artists gain the widest sort of respect and recognition within the industry.

The Doors and friends

But as significant as their discovery was and as proud as he remains of that legendary band, Holzman didn’t peak with The Doors and kept looking for new talent and searching for the new directions the music was taking. Along with the exacting producer Paul Rothchild and ace engineer Bruce Botnick, Holzman provided a home for some of the crucial acts of the 1960s and early ’70s, even if the commercial rewards were not always immediately apparent. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the MC5, and The Stooges all had their debuts on Elektra, as did the remarkable vocalist Tim Buckley and the highly influential English acid folk group, The Incredible Strung Band. As the ’70s progressed, Holzman and Elektra mined a rich vein of adult contemporary to great success with artists such as Carly Simon, Harry Chapin and Bread. But they also gave future arena rock favorites Queen its first American release, a pretty neat summation of the profound eclecticism that Holzman always deployed as both a business strategy and personal philosophy.

The book is not without flaws — it is so thoroughgoing it can run on and there is a bit too much egalitarianism in Houghton’s coverage of Elektra’s musicians so that dated novelty acts like David Peel & the Lower East Side, whose main claim to fame is an album entitled Have a Marijuana that was recorded live in the streets, get somewhat equal coverage as some of their more significant peers like Ochs and Buckley. And for my tastes I wouldn’t have minded more focus on Rock and less on Folk because that’s where my interests lie. The book is so intensely detailed that it takes a lot of pages to get from Holzman’s beginnings with Appalachian songbird Jean Richie to the exciting Love-Doors era. But leaving aside personal musical prejudices and taken as a complete retrospective of Holzman’s incredible career, Becoming Elektra tells a wonderfully engaging story about a genuinely important pioneer of the music business during three decades of rapid change and growth. If you’re at all interested in the history of music in the 1950s, ’60 and ’70s this book, which is also handsomely decked out with photos and cool album cover art, another Elektra trademark, is definitely worth a read. Jac Holzman’s amazing career makes a solid addition to anyone’s Rock library and Houghton’s exhaustive research uncovers many things that were previously hidden, as well as a lot of very entertaining backstage anecdotes. As both a biography and a historical document about 20th century music I highly recommend it. You’ll come away from it with a better understanding of the music business and how a man like Holzman shaped it through true love of the artists and a single minded determination to get as many of the ones that appealed to him recorded, released and sounding their very best. That resulted in Holzman assembling one of the broadest and most impactful music catalogs we have and Becoming Elektra lays out that historical accomplishment admirably for anyone with eyes and ears to see.