The Greatest has left us. Muhammad Ali passed away late Friday evening, succumbing to a severe respiratory infection after years of struggling with boxing-induced Parkinson’s. The great fighter and one of the most iconic and polarizing figures of the 20th Century was 74. The New York Times obit is here.

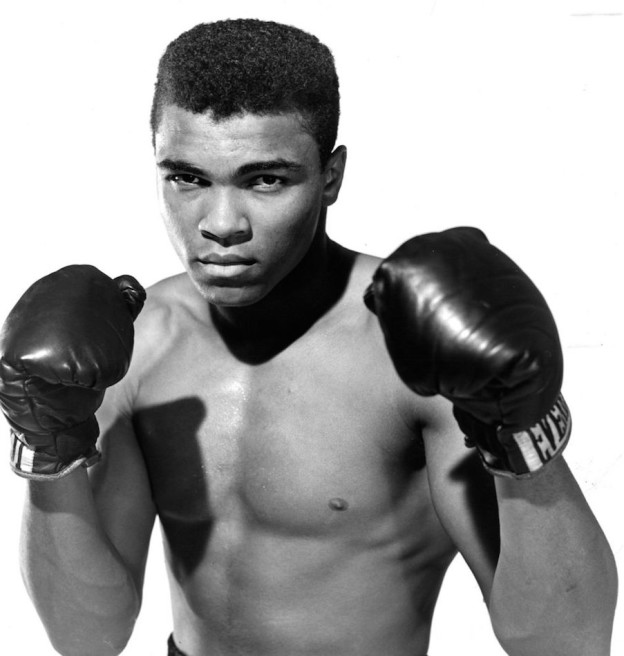

It’s easy to forget that, as Ali gradually transformed in his years after the ring into a sweet natured shadow of his former fiery self, what a wonderfully brash and divisive figure he was in the prime of his remarkable boxing career. Born Cassius Clay in Louisville, Kentucky, Ali spent his formative years in that racially divided Southern city, becoming a champion amateur fighter and winning gold as a light heavyweight in the 1960 Rome Olympics. You’d be hard pressed to find a more suitable symbiosis between personality and decade, as Ali became one of the most compelling and archetypal figures of the tumultuous 1960s, joining luminaries like the Beatles, the Kennedys and the NASA astronauts among the towering figures of that time. After his gold medal triumph, Ali returned home to open racism in his hometown but also a consortium of white businessmen dedicated to promoting his career. He discovered a bastardized version of Islam, patented his trademark rhyming patter and eventually earned a title shot against the heavily-favored Sonny Liston. In what would go down as one of the great upsets in boxing history, the lightning fast Cassius Clay floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee, driving the hulking Sonny Liston to quit in the 7th round, having punched himself out trying to keep up with the precocious youngster. As he roared to a bemused Howard Cossell, Ali truly had “shook up the world!”

He would continue to shake it up. The very next day he announced his intention to rid himself of his “slave name” thanks to the advice of his new friend and mentor Malcom X and a few weeks later he was forevermore Muhammad Ali. Already alienated by his brashness, for much of white America this bewildering and unsettling transformation was a bridge too far and Ali would come to be loathed by many as a malcontent, an “uppity Negro” with a big mouth. Even more defining and defiant, in 1966 Ali was made eligible for the draft for the escalating war in Vietnam but was clear in his reluctance to fight, saying “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong.” When drafted in 1967, he refused to serve. He was subsequently denied conscientious-objector status and convicted of draft evasion, lost his boxing titles and was banned from the sport. Ali lost more than 3 prime years in the ring and probably millions of dollars for standing up for his principles and not to fight in what he saw as an unjust war against poor people in a poor far away country. Again, this made him a hero to many in the emerging counterculture and anti-war movement and a pariah to more conservative Americans who steadfastly believed in “my country right or wrong.” But whatever one thought of Ali’s stance on the war, one had to give it to the Champ that he had the courage not only to talk the talk but also walk the walk.

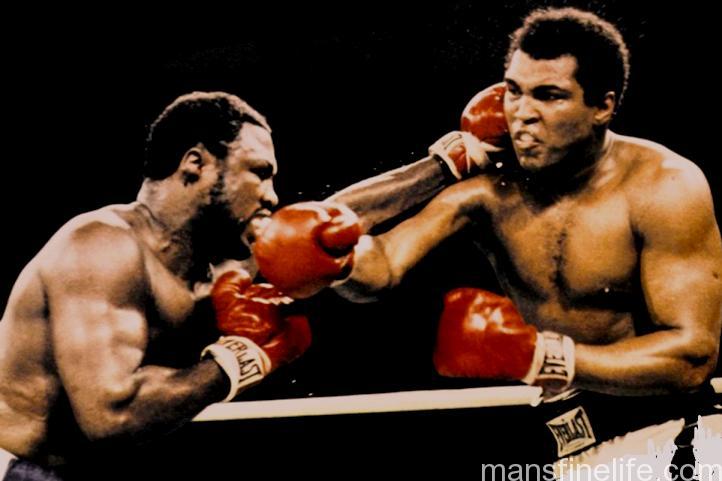

After seeing his case go all the way to the Supreme Court in 1971 and having his conviction overturned there due to the draft board’s arbitrary refusal to consider his conscientious-objector status, Ali pivoted from that moral victory and returned to his violent and lucrative vocation. He resumed his career with a series of tune-up fights in anticipation of a title shot against the fearsome Philadelphian southpaw, George Frazier. The eventual trio of Ali-Frazier fights would become some of the most compelling in boxing history, a worldwide obsession and a racial psychodrama between the handsome, light-skinned and eloquent Ali and the darker, more rugged and plain spoken Frazier. Ironically, Ali became the hero to Black America even as he taunted Frazier for looking like a “gorilla,” while Frazier drew the support of working class whites who wanted the uppity, draft dodging Ali put in his proper place.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IfUHYUpmTFs

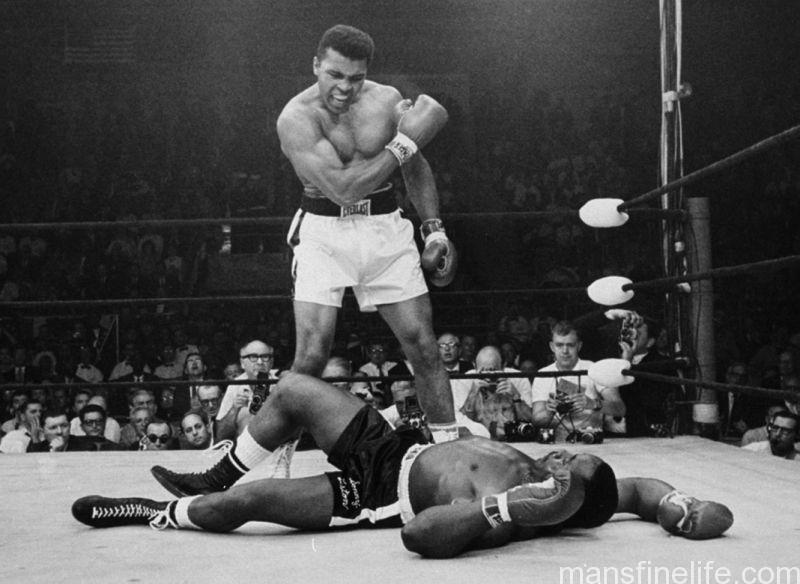

Ali lost an epic and punishing 15-rounder to Frazier in March of 1971, suffering a broken jaw but hanging on to the end in what was called simply “The Fight.” Despite the loss The Champ was clearly back. He fought brilliantly in more than a dozen more contests, including beating Frazier in a rematch in 1974. That set him up for the legendary “Rumble In The Jungle” in Zaire to try to regain his title against the imposing knockout specialist George Foreman, who had pummeled Frasier to grab the championship belt. We may think of Foreman as a smiling, grandfatherly presence now hawking his grill on TV but in 1974 he was as serious as a heart attack. Many feared that Ali would be injured against the overpowering Foreman. But as he had done against Liston all those years ago, only taking it to an even more highly polished level, Ali “rope-a-doped” his way through 7 rounds, staying just at the outside of Foreman’s punches by dancing and using the springy ropes to duck, dodge and evade the worst of the bigger man’s punishing blows, often absorbing them with his elbows and shoulders. By the 8th round Foreman was gassed and Ali used an ultra-fast combination to chop Foreman down like a mighty oak. Ali was once again The Champ and the way that he had seduced most of the African continent and turned them against the sullen Foreman with his charisma, coaxing them into giving him the psychological boost of their unbridled affection — “Ali bomaye!” — was arguably one of the most brilliant acts of gamesmanship ever seen in sports. Not only was Ali one of the most gifted athletes of his time but he was clearly also one of the wiliest.

But no boxer can last forever no matter how blessed or brilliant. Ali fought Frazier for a third and final time in 1975, the oppressively hot “Thrilla in Manila,” with the fighters doling out punishment to each other. Ali won on a TKO in the 4th round when Frazier’s eye closed but it’s safe to say that both men would carry the effects of their legendary trilogy of no quarter asked hand-to-hand-combat for the rest of their lives. In ’78 he lost and then regained his title to Leon Spinks but then in 1980 his old sparring partner Larry Holmes battered the noticeably slowing Ali into submission to take his title away for the last time. Ali closed out his career, already with signs of slurred speech and some tremor, with an ignominious defeat to journeyman Trevor Berbick in 1981. For most of Ali’s millions of admirers and even many of his detractors, the end of Ali’s boxing career, belated as it was, came as a welcome relief. It was simply too painful to watch the once-great warrior fight any more.

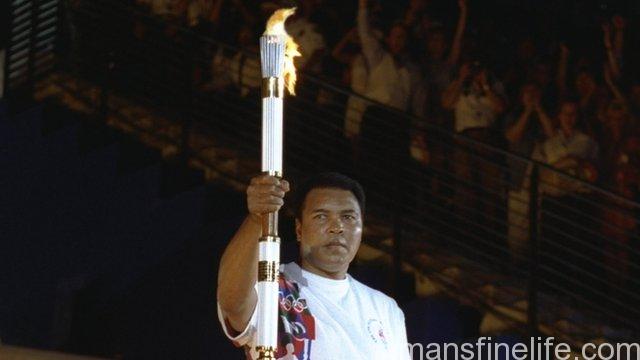

Of course it was already too late and the damage to Ali’s brain had been done. But for the remainder of his life, Ali became one of the great retired athletes of his time, right up there in terms of activism and charity with Jackie Robinson. Remaining a devout but now-mainstream Muslim, Ali did Herculean work for charity and traveled the world working for good causes. As his physical capacities diminished, one still had the sense of that agile mind floating like a butterfly slyly behind the slow-blinking eyes and the trembling hands. His rough edges were smoothed off, the controversies largely forgotten and he became something like an American legend, a beneficent but remote presence, there always around us but somehow elusive and receding. In our mind’s eye we saw one of the most vibrant athletes ever to grace the ring with personality as magnetic as any movie or rock star, nicknamed “The Lip” for his upstart self-promotional pronouncements. But in his long, last chapter Ali was a slow-moving man of peace and few words making impactful but dwindling appearances like that of his touching torch lighting at the Atlanta Olympics in 1996. It was as if his prodigious energies had been well and truly spent, leaving him running on dwindling reserve power inside his prison of a body until this last, final moment of release.

But too often we obsess over a person’s sad last days and those tend to take on disproportionate significance compared to the entirety of their lives. In the two decades of his prime and the time of his greatest impact on sports, on the nation and on the world, Muhammad Ali was both pretty and a baaad man, a beautiful, graceful athlete and proud black man, a speaker of hard truths and always of his own mind, a genius inside the ring and out. He was one of the greatest boxers of all time in the latter part of a century where boxing was one of the marquee sports. At a time when we’re often unable to name the current world champion amongst all the different belts and mediocre pugilists, it’s hard to recall just how big a deal being Heavyweight Champion of the World was back then, every bit as big as being the College Football Champion, the Super Bowl winner or the victor in the World Series. People lived and breathed boxing and Ali was the successor to other legendary heavyweights like Jack Johnson, Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano. But he was so much more than just a boxer. Ali dovetailed so beautifully with the emerging zeitgeist of Black Power, Sports as Entertainment and Sports as Symbolism that if you wrote him as a character you’d never get away with it — he would’ve been too outrageous, too perfectly well-spoken, poised and self-assured, too victorious. But Muhammad Ali was just that perfect a fit for his tumultuous times even with his flaws taken into account. Love him or hate him, you could never ignore him. He was a titan of sport, pop culture and, in fact, social change. His message, implied or stated bluntly, was Yes We Can to African-Americans and religious minorities, to the poor, the Third World and the downtrodden. When James Brown wrote “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud!” he might’ve written it with Ali in mind. Ali gave hope, light and heat to the world. As the Spanish say, he was simply muy hombre and to conceive of anyone being quite like him again in an age where athletes rarely go out on a limb for fear of alienating their sponsors seems impossible. His echo lives on in a million boasts and taunts on the court and in the field and in the ring. But everyone else is imitating him and their predictions and preening seems more like ritualized kabuki than those of true conviction and zest for the battle. Ali nearly always delivered on what he promised and by doing so he was able to make pronouncements about issues far beyond a simple sporting event. With his mouth and his mind, his brains and his guts, his speed and his strength and his unwavering sense of self, Muhammad Ali really did shake up the world. And the world’s been vibrating from the aftershocks of his impact ever since.