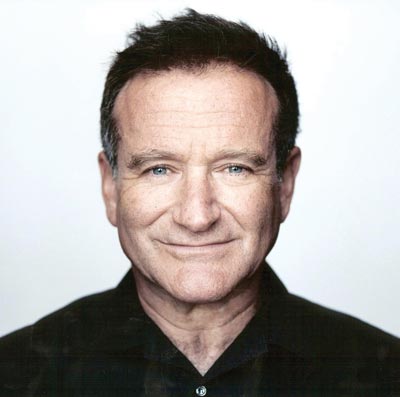

Ok, I’ve been procrastinating on posting this because it is so fucking sad. Robin Williams died this August 11th of suicide by self-asphyxiation. The great actor and comedian had been battling depression, as well as falling off of the sobriety wagon in recent years. Williams was just 63 years old. His New York Times Obituary is here and a very good A.O. Scott appraisal with video is here.

Obviously the tragic irony of one of the world’s funniest men succumbing to depression is well-trod ground by now. To think that someone that successful and accomplished could not get the help they needed to make it through the darkness is simply frightening. But in the end we often walk alone in this world and what drives an amazing artist, which Williams undoubtedly was, can come from the dark places of insecurity and sadness deep within, even if the art in question is comedy with a capital C. I can’t think of another person funnier than Robin Williams when he was at his manic improvisatory best. If a talk show appearance can be called art, Williams performed it, on Carson or Letterman or a million other venues that should never have had room for such pocket Dada free associative miniature moments of brilliance. He enlivened the most mundane show business rituals with electric bolts of inspirational lightning. The sense that he was barely in control of his manic energies only added to the thrill ride.

As the years went by, well after his comet-like appearance on the scene in the late 1970s, Williams evinced a melancholy sensitivity in movies like Good Will Hunting, Awakenings and Dead Poets Society that saw him turning into a sounding board for people in need of compassion, especially young people, and an outsider’s point of view to deal with a stifling world. But that sad smile has been there from the start like the tears of Pagliacci, at least as far back as The World According to Garp, Moscow on the Hudson and bursting to raw fruition in Terry Gilliam’s revelatory The Fisher King. That undercurrent of melancholia was probably a major part of Williams as a person when he wasn’t “on”, obscured in the early days by his irrepressible, some would say uncontrollable, daffy genius when he seemed to be very nearly Bugs Bunny come to life. To be sure, Williams felt loss and sadness keenly through the years with the deaths of such friends as John Belushi, Andy Kaufman, Christopher Reeve and, most recently, his mentor and idol Jonathan Winters. Maybe we just didn’t want to believe that such real life losses would take their toll on our favorite comedian.

A genius in more ways than one, Williams’ gift must have also been something of a curse, creating the expectation in his audience that he must deliver to them transcendental moments of hilarity on demand and at all times. You could see him rebelling against this expectation in the later years when he would slip a somber mask on in interviews and publicity junkets. But the urge to please that broader audience was always there, leading to blockbusters like Mrs. Doubtfire, the voice of the Genie in Aladdin and priceless as the gay father trying to get Nathan Lane to play it straight in The Birdcage. And yet those movies are still great even if they are down-the-middle Hollywood fare and right in Williams’ comfort zone of impersonation and mugging. In the end, they are family-style movies, much like Hook, Happy Feet and Night at the Museum, that transcend their mundanity by adding Williams’ essential ingredient, the spark of hilarious unpredictability, giving the adults plenty to laugh about along with their children as they sit through the DVD for the 10th time. One should also add Robert Altman’s Popeye to that list — at the time it was considered a huge bust, Williams’ first real career setback, but in retrospect it looks like the inspired work of two mad scientists creating an amazingly surreal and faithful live action cartoon.

Certainly Robin Williams made his share of stinkers, as anyone who worked for that long and that often will have done (I am looking at you, Mr. De Niro). But what remains are the gems of the indelible performances: the inspirational and rebellious DJ beloved by the GIs in Good Morning, Vietnam; the nonconformist prep school teacher in Poets; the tough but caring shrink in Good Will Hunting; anything but in the jet black World’s Greatest Dad; and the fantastically deranged children’s TV host Rainbow Randolph losing everything including his mind in the hilarious Death to Smoochy.

Obviously his stand-up comedy, thankfully largely preserved through myriad HBO specials, has its own magical place in any assessment of this great performer. On his best nights, the shows were a true happening and he was essentially like a comedy John Coltrane. He was also legendarily generous with his time for good causes, from being a founding co-host along with Billy Crystal and Whoopi Goldberg of the many Comic Relief fundraisers for the homeless and impoverished, to many trips overseas with the USO to entertain American servicemen and women, as well as many other worthwhile charitable works. Certainly not a perfect man, it is still clear that Robin Williams strove to do good in this world.

I remember being 10 years old and laughing my ass off at Mork & Mindy. I’m sure the 10-year old boy in me would still find it pretty funny. TV sitcoms had never seen anything quite as crazy as that first season and his wonderfully demented space alien. It’s a wonder that Pam Dawber could make it through any of the scenes without breaking up. So like a lot of people under 50, I can say I grew up with Robin Williams. He was a part of my life from when I was a kid to my young adulthood until now. When you gave up on him ever making another great movie, something would come out that was uproarious or touching. You came to realize, even if begrudgingly, that he was just as good in serious stuff as in the funny stuff you always wanted to see him doing. And when he was booked on the late night talk shows, that became appointment viewing. You never knew what he’d do but more often than not it was something brilliant. Even as he shied away from the madman genius persona later on, sometimes coming across as almost sedate at first, there would be something killer once he got warmed up. And sometimes, in those fleeting televised moments, he was simply transcendent, a man working high up without a wire and bringing it off beautifully.

So a part of my childhood died with Robin Williams the other day. As maudlin as that sounds it’s still true and I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling that. A national treasure, a friend for life, a bit of delightful madness in this straight-laced world has gone out of all of our lives. It is ineffably sad the way he departed and sadder still that his lifetime body of work, a magnificent achievement in toto and a source of unmitigated joy in so many ways, will now have a bittersweet quality attached to it. I have a fear that when I see his wonderful art in future my heart might still hurt. I know that should pass and I’ll be grateful for all the gifts he did leave behind during his lifetime but I admit that I haven’t been moved by the death of a celebrity to this extent in a long time, maybe since John Lennon or Hunter Thompson. But maybe only since Philip Seymour Hoffman and that too-fresh grief at the loss of another truly gifted artist is simply making this worse. I respect a man’s right to take his own life on his own terms and to not have to face growing old, losing the spark and becoming enfeebled. Maybe with his return to addiction and health issues these last several years, Robin Williams feared that inevitable decline. Maybe he wondered if his best creative years were behind him or if his work had any real meaning. Maybe he was so disgusted with his relapse that it engulfed him in depression too suffocating to be fought through successfully. Maybe he had just been “Robin Williams” for too damn long. Whatever the root cause of his last fatal bout of mental illness, he decided to end it all. I surely wish he hadn’t because I know, absolutely know, that he had many more years of joy left to give to the world. After all, that was and remains his greatest and most lasting gift. To take away that future Robin Williams from us forever is a hard thing to deal with for those of us who are left behind. Unique is not a strong enough word for what he was and now that’s gone for good.

When a celebrity dies, much as when they live, all of the tributes, sightings, opinions really reflect the person telling the anecdote. We co opt the event for our own motives and needs to be be a part of it. Or worse, hold it up as a cautionary tale with a “teachable” moment. Rarely does a tribute have such insight to encompass the deeper universal meaning of the loss while respecting the individual without judgement at the center of it. This real person with real pain. This is the first piece besides Lewis Black’s that has comforted me in any way. Thanks, Tom.

Deep sentiments well stated.