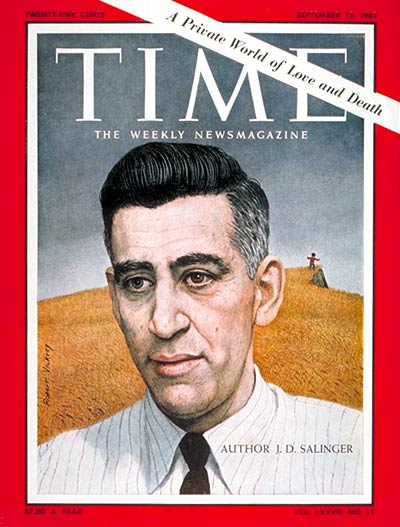

One of the literary world’s great mystery men, J.D. Salinger famously disappeared from public view in 1965, when his last work was published and 14 years after the release of The Catcher in the Rye, arguably the most influential novel of the post-World War II era. Immensely private almost to the point of mania, Salinger’s opaque personal history and life in seclusion have fascinated generations of fans, literary peers, critics and the media. Shane Salerno’s 2013 documentary Salinger, which can be viewed via streaming with a Netflix membership, attempts to “find” the reclusive author by investigating and fleshing out his pre-fame life and examining the motives behind his self-imposed exile after achieving literary immortality. For the most part, it succeeds extremely well at this daunting task.

Not a great documentary but a pretty damn good one, Salinger features interviews with lifelong friends and acquaintances dating back to his pre-WW II days in New York City when he was just an aspiring writer striving for success and any sort of recognition. Significantly, it explores his engagement to the fetching debutante Oona O’Neill, Eugene O’Neill’s daughter, who eventually dumped Salinger for the much older Charlie Chaplin. Shortly thereafter Salinger was sent to Europe as a combat soldier in the Army. Salinger saw action on D-Day, in the Battle of the Bulge, the Battle of Hurtgen Forest and was at the liberation of one of the Dachau concentration camps. The documentary posits convincingly that it was these twin traumatic experiences, particularly his harrowing war service, which informed all his future work and lead to his compulsive focus on unspoiled youth, eventually driving Salinger to seek to create and control his own private universe.

It also chronicles how he was constantly submitting to and being rejected by his dream venue, The New Yorker, before during and after the War, even as he achieved modest success in the so-called “slick” magazines. He finally found a sympathetic figure at the The New Yorker in fiction editor William Maxwell, who agreed to publish “A Perfect Day for Bananafish”, which became a major success. It also introduced the world to the brilliant and strange Glass family through its troubled eldest son Seymour Glass, a shell-shocked war veteran. The history of the Glass family would later become Salinger’s lifelong obsession. But before that detour, several more short stories were published by the New Yorker, including “Uncle Wiggly in Connecticut”, which Salinger eagerly optioned to Hollywood for a film version. The result, a Dana Andrews-Susan Hayward romantic vehicle retitled My Foolish Heart, was so unfaithful to his original story that Salinger never again allowed a film version of his work despite his obsessive love of cinema and constant entreaties from producers, directors and actors.

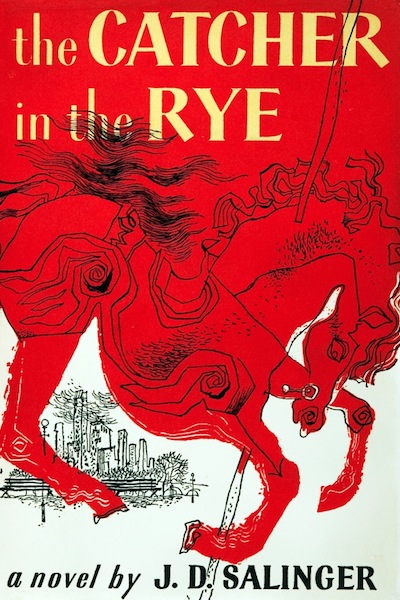

But if Salinger was smarting over Hollywood’s betrayal he put that anger to good use, channeling his rage at the “phonies” into the archetypal youth novel, The Catcher In the Rye. Published in 1951, Catcher seemed to tap into an entirely new and previously unarticulated current bubbling under the straight-laced, post-War faux-wholesome era of the burgeoning 1950s. Its first person narrator was the teenaged Holden Caulfield, adrift in Manhattan after expulsion from prep school and haphazardly pursuing a series of misadventures while desperately seeking authenticity at the border of the confusing and duplicitous adult world. The novel beguiled readers with its frankness, deep sensitivity and passionate opposition to the “phonies” of the world. It attracted droves of youthful followers and can be said to have been the prototype and conscious or unconscious inspiration for James Dean and Rebel Without a Cause, youth rebellion throughout the 1950s and even the hippies and flower children of the 1960s. It continues to be one of the most influential books ever written in the English language, an inspiration and a right of passage for young people today despite being banned in many schools.

The film also delves into how Catcher possibly inspired a darker element, including Mark David Chapman, David Hinckley and Robert John Bardo. But then, having sold at least 250,000 copies every year since its publication, there are bound to be a few wackos that attach themselves to such a transformative work. More convincing is the documentary’s linkage of Salinger’s wartime service and probable PTSD in inspiring both his writing as a whole and also his eventual self-imposed isolation, where he would write endless fiction, often about wartime experiences, in a private bunker-like studio at his compound in Cornish, NH. It is clear from a story like “Bananafish”, where Seymour Glass abruptly ends his life and marriage with a self-inflicted gunshot in a Florida hotel room, that there are demons simmering beneath Salinger’s otherwise sprightly and urbane prose. In fact, I would go so far as to theorize that J.D. Salinger’s absolute obsession with the Glass family post-Catcher, which reached its zenith with the novella Franny & Zooey and its nadir with the nearly unreadable “Hapworth 16, 1924” (his last published work), is in fact an effort to justify killing off Seymour so cavalierly in his first great short story. Perhaps by keeping the Glasses forever alive in his stories and endlessly relitigating Seymour’s graceless exit he was trying to rescue not only his literary blunder but also the younger version of himself that he had killed, as well. But I digress…

Regardless of any stars or ratings given for style points, Salinger will be a must-watch for anyone even remotely interested in the great and now late author. In often discomfiting ways, it tells the story of a brilliant artist gradually retreating into self-absorption and the stifling requirement for total control in a world that cannot possibly cooperate after the genie of his fame was willfully unleashed. If it has a few too many recreated sequences of a shadowy “Salinger” smoking at the typewriter and a few too many of the same still photos of the author pitched at different angles used to illustrate various sequences, those flaws probably have to be chalked up to the subject’s very inaccessibility and the dearth of either moving or even still pictures of the author. The sequences of Salinger’s wartime experiences are tough, sobering and lead to a much better understanding of the man and his later issues. The tales from lovers and family members who have fallen out with the him and seen his feet of clay are not so much gossipy as melancholy, pointing to a repeated pattern of relationships with young, “virginal” women, although of course one always has to take such information with a grain of salt. But no doubt J.D. Salinger was a troubled soul, as so many great artists are. At the pinnacle of his fame, something he once aspired to and dreamed of, he decided to write only for himself, willfully denying the world his gifts.

With his passing, the film dares to speculate that his magic safe full of unpublished manuscripts will be released to the world someday soon, with more stories to come of the Glass family and a bygone New York City, as well as soldiers in World War II. Judging by the deterioration of the later work, it is probably best not to expect too much from such writing. A writer without an editor is usually no better than a self-indulgent child. But then again, any work by Salinger will demand to be read, even if it is only as good (or bad) as a “Hapworth”. Such is the legacy of this brilliant author. And, as a friend and fellow enthusiast remarked to me, despite the documentary Salinger‘s stylistic shortcomings, it demands to be seen and seen again. Like the printed works, it’s all we’ve got and all we’re likely to ever get.