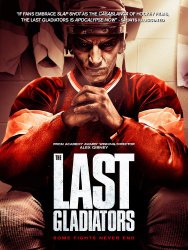

Since it’s that ultra-exciting time of year known as the NHL Stanley Cup Playoffs, it seems fitting that we take a look at Academy Award-winning director Alex Gibney‘s 2011 documentary, The Last Gladiators. This compelling and viscerally satisfying examination of hockey’s most feared enforcers is also a paradox, serving as both cautionary tale and celebration of professional hockey’s unique culture of acceptable violence and the men who best practice it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-y9i9RxX7Qw

With unprecedented access to the toughest men to play the game, Gladiators’ main focus eventually settles on Chris “Knuckles” Nilan, a hard-nosed kid from Boston whose NHL dream came true as a beloved character on the 1986 Stanley Cup-winning Montreal Canadiens, the NHL equivalent of the New York Yankees. With relentless bravado and aggression, Nilan stepped into the fray to defend his more skilled teammates from other teams’ taking liberties, the key function of the enforcer, and went toe-to-toe with the toughest guys of his era. Craving validation as more than just a goon, Nilan even scored 21 goals in his best season under legendary coach Jacques Lemaire. But as it does with many athletes, Nilan’s career slowly declined due to injuries and, after a decent stint with the New York Rangers, petered out unhappily with his hometown Boston Bruins, where the the former Canadien was viewed with deep ambivalence.

The fascinatingly complex star of the film’s many present day interviews and great historical clips, the older Nilan comes across as extremely intelligent, self-aware and still quite cocky. He is also clearly someone who cannot control his more unpleasant impulses in civilized society and, as someone who lived by his own code on the ice, cannot submit himself to authority. After his playing days ended, he was unable to keep a job in the NHL because of his inability to respect the assistant coach’s subordinate role, even while working alongside his favorite head coach, Lemaire. He then struggled to find steady conventional work and was reduced to taking odd jobs and playing in old-timers games. In one instance, we see him violently cursing out some amateur goalie as if he were baiting the Philadelphia Flyers in a big game.

It comes as no surprise that Nilan admits to a descent into drug & alcohol abuse, with an unsurprising addiction to prescription painkillers but also to heroin to ease the pain from years of physical abuse and the mental pain of losing his life’s avocation. But what is also likely in evidence here even if it is never mentioned directly is that Nilan is being affected by Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a relatively recent formal diagnosis linked to repeated brain traumas. While mainly identified with football, it’s obvious that hockey players in their collision-oriented sport are also succeptable to its debilitating effects, including mood swings, premature dementia and suicidal depression, often paired with self-medication via drugs and alcohol. This seems especially true of the fighters in the sport. We now know via autopsy that Rangers’ enforcer Derek Boogard, who overdosed after struggling with depression at the age of 28 in 2011, had CTE. Likewise, that same year tough guys Wade Belak of the Toronto Maple Leafs and Rick Rypien of the Vancouver Canucks both committed suicide, indicating severe depression most likely brought on at least in part by CTE.

Nilan’s own contemporary, rival and sometimes friend, the fearsome Bob Probert, died of a heart attack at the age of 45 after well-publicized drug problems and was also found to have CTE post mortem. As if for posterity, Probert is interviewed for The Last Gladiators along with several other top level fighters such as the charismatic Tony Twist and those mortal adversaries, Donald Brashear and Marty McSorley, forever linked by McSorley’s infamous cheap shot.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lvDk7jtNNhc

While CTE is not limited to the fighters of the sport by any means — the number of concussions is key — it’s easy to imagine these pugilists being more at risk as a result of their hard duty protecting their teammates. So even if Chris Nilan’s own father uncharitably describes his son as having “thrown it all away,” Nilan’s erratic post-hockey behavior is not happening in a vacuum and probably doesn’t spring solely from his personal failings. In its traditional incarnation, North American hockey’s unique culture demands that there be blood on the ice for transgressions against the unwritten code: If there is a wrong done to one team’s skill players — or even if a team is trailing by too many goals — that team’s toughest guy will challenge the designated fighter of the other team to a fist fight, a plot as predictable as kabuki theater. Often these brawlers are kept on the roster for no other reason then their fighting prowess. But it can be argued that nothing excites the fans more or rallies teams more effectively than two hard men throwing down their gloves and duking it out until one of them goes down. This is the price Nilan and his ilk were willing to pay for our entertainment and for their own notions of honor, loyalty and glory. They paid it willingly to make it to the big time and no doubt reaped the rewards of fame and fortune from their pugilistic exploits. And now, as they grow older, they may have to pay the even steeper price of their mental and physical health. As we learn more about CTE in contact sports one wonders if the perennial murmured talk of banning fighting in pro hockey, as it is banned in the college and international versions, might actually come true. If so, the fierce warriors on skates depicted in this excellent documentary might be The Last Gladiators after all. And we may one day look back and wonder that their glorious savagery was ever considered such an integral part of the great sport of hockey at all.