When it comes to paranoid film thrillers, the 1960s and 70s were the golden age. And John Frankenheimer’s 1964 classic Seven Days in May was perhaps the grandaddy of them all. Now, you can argue that Frankenheimer’s undisputed masterpiece The Manchurian Candidate, released two years earlier, was actually the prototype for the cinema’s soon-to-be omnipresent conspiracy-minded neurosis. But while Candidate does involve a horrifying plan to bring down the US government, the key difference is that in Seven Days in May that threat is coming from inside the country.

Spoilers below the fold…

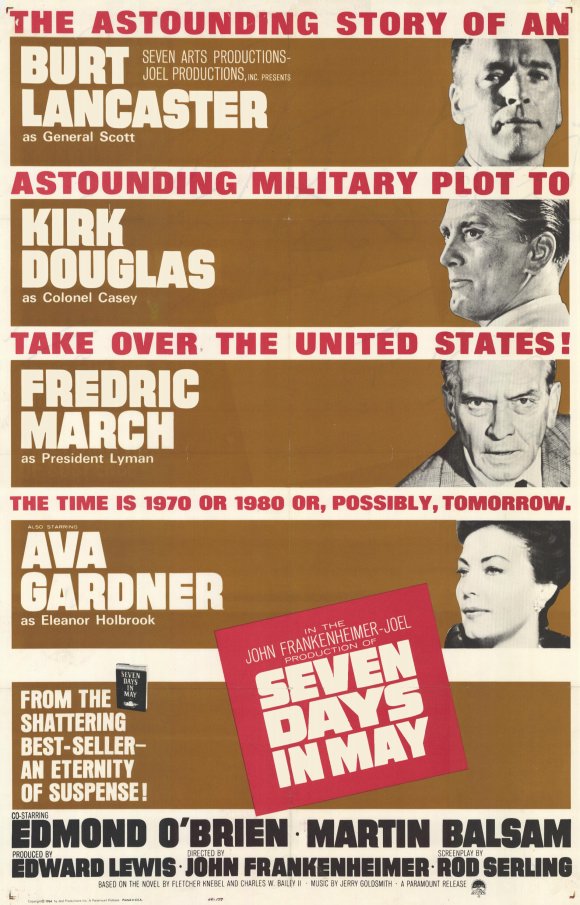

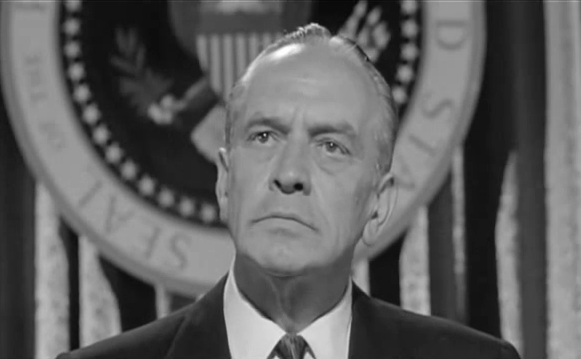

Specifically, the threat involves a planned military coup d’ etat by MacArthur-like General James Mattoon Scott, played with icy intesity by the peerless Burt Lancaster. Scott, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, sees himself as the savior of the nation and sets in motion a plot to remove what he sees as a fatally weak and unpopular president, Jordan Lyman, who has just signed a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Russians. Along with the other service heads, who share his disdain for the negotiated settlement and view it as leaving the US irreparably vulnerable, Scott concocts a secret plan to remove President Lyman, played with shrewd intelligence and brio by the veteran star Fredric March, to be initiated by an order to a secret army unit, ECOMCON, to seize all the media and communications channels of the United States, broadcast word of the “necessary action” to the general public and subsequently have congress reject the nuclear treaty.

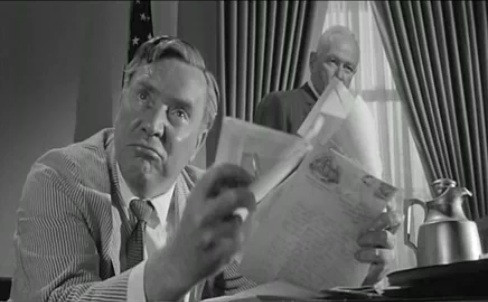

However, General Scott’s attache at the Pentagon, Colonel “Jiggs” Casey, soon determines that something strange is going on when he cannot get an answer for what ECOMCON is or even that it exists. “Jiggs”, played with typical clenched-jawed intensity by the incomparable Kirk Douglas, is further alarmed when a junior officer in codes & cyphers alerts him to the existence of a far-reaching and secret “office pool” for the Preakness Stakes in which only the most senior military officials seem to be participating and only with yes or no answers. After seeing General Scott give an ambitious, demagoging performance at a political convention in New York, “Jiggs” brings his well-founded concerns to President Lyman. The film only gets more intense from there, as “Jiggs” and a small group of political operatives loyal to the president work feverishly to uncover and discredit a potentially history-altering plot by the most powerful military men in the nation.

Along with Lancaster, Douglas and March, Seven Days in May also features standout supporting performances from Martin Balsam as a loyal aide to the president; the wonderful Edmond O’Brien as an alcoholic but cunning pro-Lyman Southern Senator; and a middle aged but still ravishing Ava Gardner as the vulnerable former mistress and potential Achilles’ heel for the otherwise self-righteous General Scott. And auteur John Frankenheimer cements his place as one of the great directors of creeping dread and suspense, aided by well-chosen location shots of Washington, DC and the richly atmospheric, almost documentary-like black and white cinematography of the relatively unheralded Ellsworth Fredricks. If Frankenheimer had made only Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days I think he would still be considered a major director. The fact that he also made such other stone classics as The Train, Grand Prix, Seconds, The French Connection II, Black Sunday and his late career masterwork, Ronin, puts him amongst the best all-time at thought-provoking and viscerally entertaining action moviemaking. It’s also no coincidence that they all feature standout acting from their male performers — Frankenheimer had an amazing way of getting the best from superstar actors. As great as these films are, I still feel that John Frankenheimer is underappreciated. In fact, he was never nominated for a Best Director Oscar during his 45-year-career in movies.

With a screenplay by Rod Serling derived from a best-selling novel by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey, Seven Days in May definitely has that through-the-lookinglass Twilight Zone feel to it and was certainly a response to the Cold War saber rattling of staff officers like Curtis LeMay, who advocated preemptive nuclear strikes on the Soviet Union, as well as the popular if undemocratic urge for a Caesar-like “Man on a White Horse” to save the country, embodied by great generals of the recent past like MacArthur and Patton. It’s very plausibility is what makes it so spine-tingling, as it capitalizes on the prevailing mood of barely surpressed hysteria that so epitomized the years leading up to and immediately following the Cuban Missile Crisis. Along with the grim Fail-Safe and the uproroius Dr. Strangleove, Seven Days ushered in an era of paranoid, doubtful cinema that led directly to later deeply unsettling thrillers like The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor and Capricorn One. And like all great classic movies, it becomes an old friend that rewards repeated viewings, well worth revisiting every few years to experience again such a masterful confluence of acting, writing and direction.

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic post. Fantastic.