We’ve all seen every James Bond movie multiple times and have our own firm opinion on who is the best Bond — Connery? Moore? Craig? Brosnan?? But how many have read the original Ian Fleming novels? Well, if you’re a true Bond aficionado you really should check them out. And if you’re looking for enjoyable, action-packed summer reading it’ll be a win-win. While the films jump off to an entirely more fantastical level and become their own distinctly grandiose vision of 007, the stripped-down genesis of the Bond phenomenon is in the books. There isn’t close to the gadgetry in Fleming’s original conception, although there are some impressively explosive high-concept climaxes, and the bon mots are a little more subtle. Bond himself tends to be more grim, fallible and vulnerable and less of an glibly unstoppable killing machine than in the films. He comes across as a diligent, well-trained espionage professional with above average self-defense skills and an expert with firearms, a top agent with a sharp, opportunistic mind and a cold reserve covering up signs of doubt and melancholia. It’s a definite key to Daniel Craig’s success that his Bond hews more closely to Fleiming’s original dour conception.

Ian Fleming’s own early drawing of Bond (pic from Wikipedia)

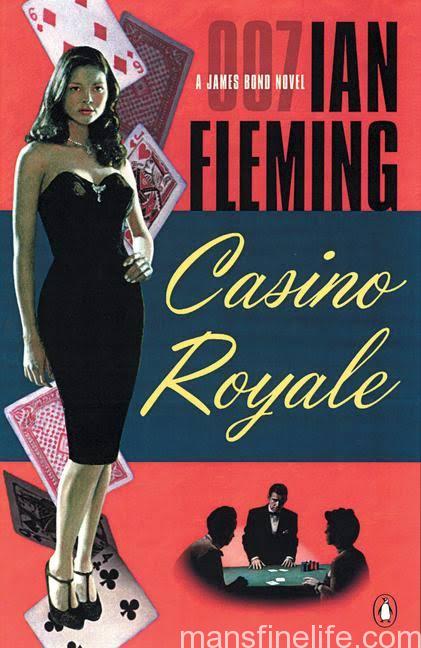

The first novel in Fleming’s massively successful opus is the notorious Casino Royale. I say notorious primarily because the film rights were tangled up for so long that it was the only Bond novel not to make it to the big screen… in recognizable form — the very poor 1967 Woody Allen-David Niven parody shares only the name. It took more than half a century for it to be properly adapted for the cinema via 2006’s explosive blockbuster, Craig’s excellent debut and a film many Bond fans consider one of the best in the franchise. Coming as it did after the ever more elaborate and bloated Brosnan films (although one could see some darker foreshadowing in his last, Die Another Day, where Bond is subjected to harsh torture at the hands of the North Koreans), it was no accident that finally having secured the rights to Fleming’s elusive first work, Broccoli & Co.’s franchise reboot would also try to stay true to the elements that made the start of the Bond story so special. But Casino Royale was also notorious when it was published in 1953 for its violence and sexual content, as well as the very frank and graphic way Fleming approached both issues, with many critics lining up to deride it as pornographic garbage. More than 60 years on it’s Fleming who has the last laugh because his debut novel still holds up very well.

In Casino Royale the novel we meet Bond for the first time, a WWII naval veteran (presumably an ex-commando) and now an agent in England’s Secret Service with a Double-0 classification, which, as we all know, is a license to kill on behalf of the British government. Bond is summoned by the stone-faced M., an ex-admiral and now head of the MI6 as well as Bond’s cold surrogate father figure, and given orders to initiate a plot to undermine a high-level Soviet agent in France, a communist party trade union commissar and notorious gambler, Le Chiffre. Since he originally debuted at the height of the Cold War, Bond’s first great enemy organization was in fact Soviet Russia and not yet the more nebulous SPECTRE. This reflects Fleming’s own personal political beliefs as well as the raging (and justifiable) paranoia of the day that British institutions were being infiltrated and undermined by communist spies. But Fleming also mined his experience as a war time naval intelligence officer on the home front concocting plans to be carried out in theater by special forces units, aka his “Red Indians,” to transfer the danger and excitement of the deadly espionage “game” into his writing, infusing it with that tingling sense of life on the edge in service to a patriotic cause above and beyond oneself. The game leitmotif is even more pronounced when Bond receives his assignment to pose as a wealthy Jamaican-based businessman and get into a contest of Baccarat (not Poker, as in the film) with the expert gambler Le Chiffre in order to fully bankrupt the Soviet agent, who has already been embezzling party funds for his own enrichment. Should Bond succeed, there is no doubt in MI6’s mind that retribution will be visited on Le Chiffre for his transgressions by the feared enforcement unit of the Soviet spy apparatus, SMERSH (based on a real WWII Russian counter-espionage group and an acronym for “Death to Spies”).

As Bond gears up for his creative mission, which utilizes his professed pleasure in and skill at gambling to force a showdown with Le Chiffre at the fictional Royale-les-Eux casino in the north of France, we meet his team of helpers on the good guy side. There’s Mathis, a worldly wise and sardonically funny agent of the Duxieme Bureau (again a war time name for the French secret service); Felix Leiter, a gangly, straw-haired and very wry Texan from the CIA who helps Bond out with a crucial infusion of funds when Bond’s luck appears to have run out at the Baccarat table; and Vesper Lynd, the beautiful personal assistant to Head of Section S (the section of MI6 responsible for Soviet operations) sent to add to Bond’s cover and assist him in the field. And of course, after a rocky start with Bond’s ingrained sexism dismissing Vesper as a needless distraction (“Women were for recreation. On a job, they got in the way…”) it’s only natural that they should begin to have feelings for each other during their intense trial-by-fire.

Fleming’s original Bond car (pic via jamesbondwikia.com)

Fleming’s Bond trademarks were all born here in Casino Royale: Bond’s special, souped up automobile, in this case a powerful old 1933 4-1/2 liter Bentley with a supercharger; a series of potentially life threatening scrapes avoided by skill and sometimes pure luck, including a failed bombing attempt in the town center and an attempted assassination at the tables by a concealed gun in a walking stick; Bond’s rather self-destructive smoking and drinking habits (definitely based on Fleming’s own); and a masterful command of tense situations like the brilliant, long gambling duel with Le Chiffre at the casino’s high-rollers table, where the other participants come alive and the villains are easily recognizable by their physical repulsiveness. Additionally, Casino Royale sees the debut of Bond’s signature “shaken not stirred” vodka Martini garnished with a lemon peel, which Bond christens the “Vesper” in honor of his lovely and complex companion, as well as Bond’s minor obsessions with fine clothes, haute cuisine and top shelf wines, which he explains away as a side benefit of his job that also relaxes him and a byproduct of paying so much attention to details in his professional life.

But most of all there is the debut of Bond’s trademark “how is he going to get out of this?” moment of ultimate danger and risk. In Casino Royale it comes when Bond is seemingly victorious but must suddenly leap to Vesper’s rescue after she is kidnapped by a desperate and depraved Le Chiffre. Bond plunges head long into the pursuit, falls into a trap and is captured. He is then brutally tortured by Le Chiffre to make him give up the funds he has won, and is only saved by a fluke that is no doing of his own. During his recovery from his savage beating (to his genitalia it must be emphasized) Bond and Vesper fall deeply in love. Bond contemplates retiring from the Secret Service to “stop playing Red Indians, ” as he tells a skeptical Mathis, and Bond and Vesper enjoy a passionate but uneasy retreat to a quiet seaside getaway, completing the last of Bond’s physical recovery, if not quite a total psychological one. Obviously, if you’ve seen the movie, you’ll have a good idea of how Casino Royale ends, although the precise circumstances are different in the book. But it is this final tragic climax that brings Bond back to his true calling as an agent for Queen and country, seeming to burn away the last of his doubts and softer human feelings. By the end of the first novel, Bond has not only reintegrated as 007 but is the hardened, cynical agent that we have come to know and love and that Fleming felt was absolutely necessary to the defense of the realm. The last line leaves no doubt of his ultimate toughening up.

As a piece of literature, Casino Royale is above average but not perfect. There is a definite pulpy quality to Fleming’s earliest effort, although this is more than offset by the refreshing slap-across-the-face quality of his descriptions of violence — “a ghastly rain of pieces of flesh and shreds of blood-soaked clothing fell on him and around him” — and sexual desire — “And now he knew that … the conquest of her body, because of the central privacy in her, would have the sweet tang of rape.” And there are some ticks that a good editor should have eliminated, most notably the repetitive use of the very British “directly,” as in “Directly Bond had started playing that maximums” or “Directly Bond made his way to the casino.” But there is also a pleasantly lean Chandler-esque quality to Fleming’s prose, a punchy economy of style that serves him well in both longer expository passages — Bond’s long explanation of the rules of Baccarat is both breezy and informative for the novice reader, not to mention pivotal to the action to come — as well as the sudden bursts of brutal action. Strongest of all is Fleming’s verisimilitude in describing the nuts and bolts of spycraft, as well as the greater chess game afoot and the unpredictability of the opposition. And Flemimg would get better as a writer, as he continued to develop Bond with ten other full books and two novellas.

Sadly Fleming passed away of heart failure in 1964 before he could complete any more. He was only 56, a victim of the hard living that he so romanticized in Bond. But because of the overwhelming cinematic impact of his great creation, James Bond would become a global cultural icon, the epitome of the man of action, a consummate ladies’ man and supremely British practitioner of Hemingway’s ideal of “grace under pressure.” And that monumental institution all began with a clever little mid-1950s pot-boiler called Casino Royale. Read it for yourself this summer on the beach or in a hammock and no doubt you’ll be well on your way to consuming all the original Fleming Bond novels — they are as addictive as candy. In its stripped-down literary version there is a spareness and humanness that comes through that isn’t possible with the giant eye-popping action-adventures that the movies ushered in. In truth, the films are so creatively visual that you can make a case that they transcend Fleming’s original conception, that Bond’s true greatness was only possible through the magic of cinema and the brilliance of Broccoli & Saltzman and the raw charisma of Sean Connery. But all that Bond ever was and would become is right there on those simple pages of black and white, just as enjoyable to experience in its own way as any of the movies. Casino Royale holds that special place in the pantheon as the book that lit the fuse that would detonate the incredibly explosive and resonant James Bond phenomenon. Simply put, its a must-read for any Bond fan worth his salt.